A chromosomal loop anchor mediates bacterial genome organization - Nature.com

Abstract

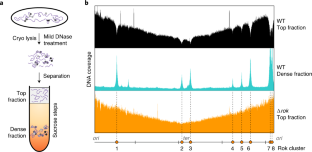

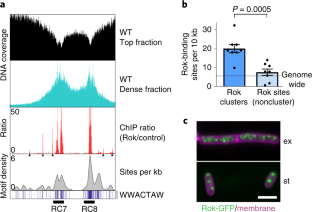

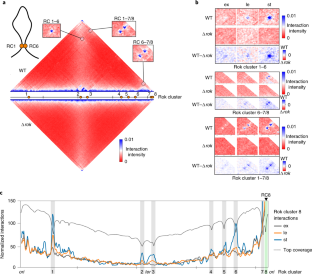

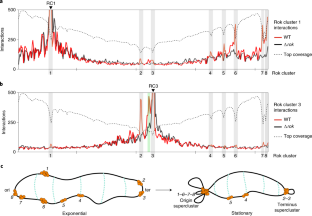

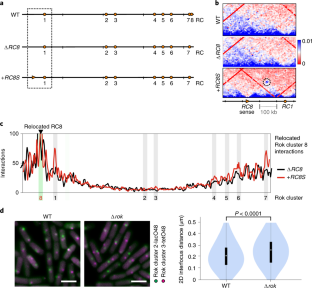

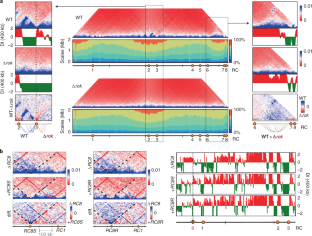

Nucleoprotein complexes play an integral role in genome organization of both eukaryotes and prokaryotes. Apart from their role in locally structuring and compacting DNA, several complexes are known to influence global organization by mediating long-range anchored chromosomal loop formation leading to spatial segregation of large sections of DNA. Such megabase-range interactions are ubiquitous in eukaryotes, but have not been demonstrated in prokaryotes. Here, using a genome-wide sedimentation-based approach, we found that a transcription factor, Rok, forms large nucleoprotein complexes in the bacterium Bacillus subtilis. Using chromosome conformation capture and live-imaging of DNA loci, we show that these complexes robustly interact with each other over large distances. Importantly, these Rok-dependent long-range interactions lead to anchored chromosomal loop formation, thereby spatially isolating large sections of DNA, as previously observed for insulator proteins in eukaryotes.

This is a preview of subscription content

Access options

Subscribe to Journal

Get full journal access for 1 year

59,00 €

only 4,92 € per issue

Tax calculation will be finalised during checkout.

Buy article

Get time limited or full article access on ReadCube.

$32.00

All prices are NET prices.

Data availability

All raw and processed sequencing datasets generated during this study can be accessed at Gene Expression Omnibus repository under accession number GSE144475.

Code availability

All source code used in this study has been published before and is referenced in the Methods section.

References

- 1.

Le, T. B. K., Imakaev, M. V., Mirny, L. A. & Laub, M. T. High-resolution mapping of the spatial organization of a bacterial chromosome. Science 342, 731–734 (2013).

- 2.

Toro, E. & Shapiro, L. Bacterial chromosome organization and segregation. Cold Spring Harb. Perspect. Biol. 2, a000349 (2010).

- 3.

Wang, X., Llopis, P. M. & Rudner, D. Z. Organization and segregation of bacterial chromosomes. Nat. Rev. Genet. 14, 191–203 (2013).

- 4.

Lioy, V. S. et al. Multiscale structuring of the E. coli chromosome by nucleoid-associated and condensin proteins. Cell 172, 771–783 (2018).

- 5.

Szabo, Q., Bantignies, F. & Cavalli, G. Principles of genome folding into topologically associating domains. Sci. Adv. 5, eaaw1668 (2019).

- 6.

Lieberman-Aiden, E. et al. Comprehensive mapping of long-range interactions reveals folding principles of the human genome. Science 326, 289–293 (2009).

- 7.

Sexton, T. et al. Three-dimensional folding and functional organization principles of the Drosophila genome. Cell 148, 458–472 (2012).

- 8.

Le Gall, A., Valeri, A. & Nollmann, M. Roles of chromatin insulators in the formation of long-range contacts. Nucleus 6, 118–122 (2015).

- 9.

Ong, C. T. & Corces, V. G. CTCF: an architectural protein bridging genome topology and function. Nat. Rev. Genet. 15, 234–246 (2014).

- 10.

Parelho, V. et al. Cohesins functionally associate with CTCF on mammalian chromosome arms. Cell 132, 422–433 (2008).

- 11.

Brasset, E. & Vaury, C. Insulators are fundamental components of the eukaryotic genomes. Heredity 94, 571–576 (2005).

- 12.

Rubin, A. J. et al. Lineage-specific dynamic and pre-established enhancer-promoter contacts cooperate in terminal differentiation. Nat. Genet. 49, 1522–1528 (2017).

- 13.

Dixon, J. R., Gorkin, D. U. & Ren, B. Chromatin domains: the unit of chromosome organization. Mol. Cell 62, 668–680 (2016).

- 14.

Le, T. B. & Laub, M. T. Transcription rate and transcript length drive formation of chromosomal interaction domain boundaries. EMBO J. 35, 1582–1595 (2016).

- 15.

Dame, R. T., Rashid, F. Z. M. & Grainger, D. C. Chromosome organization in bacteria: mechanistic insights into genome structure and function. Nat. Rev. Genet. 21, 227–242 (2019).

- 16.

Hirano, T. Condensin-based chromosome organization from bacteria to vertebrates. Cell 164, 847–857 (2016).

- 17.

Wang, X., Brandão, H. B., Le, T. B. K., Laub, M. T. & Rudner, D. Z. Bacillus subtilis SMC complexes juxtapose chromosome arms as they travel from origin to terminus. Science 355, 524–527 (2017).

- 18.

Lioy, V. S., Junier, I., Lagage, V., Vallet, I. & Boccard, F. Distinct activities of bacterial condensins for chromosome management in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Cell Rep. 33, 108344 (2020).

- 19.

Takemata, N., Samson, R. Y. & Bell, S. D. Physical and functional compartmentalization of archaeal chromosomes. Cell 179, 165–179 (2019).

- 20.

Marbouty, M. et al. Condensin- and replication-mediated bacterial chromosome folding and origin condensation revealed by Hi-C and super-resolution imaging. Mol. Cell 59, 588–602 (2015).

- 21.

Schoenfelder, S. & Fraser, P. Long-range enhancer–promoter contacts in gene expression control. Nat. Rev. Genet. 20, 437–455 (2019).

- 22.

West, A. G., Gaszner, M. & Felsenfeld, G. Insulators: many functions, many mechanisms. Genes Dev. 16, 271–288 (2002).

- 23.

Brunwasser-Meirom, M. et al. Using synthetic bacterial enhancers to reveal a looping-based mechanism for quenching-like repression. Nat. Commun. 7, 10407 (2016).

- 24.

Smirnov, A. et al. Grad-seq guides the discovery of ProQ as a major small RNA-binding protein. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 113, 11591–11596 (2016).

- 25.

Fernandez-Martinez, J., LaCava, J. & Rout, M. P. Density gradient ultracentrifugation to isolate endogenous protein complexes after affinity capture. Cold Spring Harb. Protoc. https://doi.org/10.1101/pdb.prot087957 (2016).

- 26.

Seid, C. A., Smith, J. L. & Grossman, A. D. Genetic and biochemical interactions between the bacterial replication initiator DnaA and the nucleoid-associated protein Rok in Bacillus subtilis. Mol. Microbiol. 103, 798–817 (2017).

- 27.

Hoa, T. T., Tortosa, P., Albano, M. & Dubnau, D. Rok (YkuW) regulates genetic competence in Bacillus subtilis by directly repressing comK. Mol. Microbiol. 43, 15–26 (2002).

- 28.

Albano, M. et al. The rok protein of Bacillus subtilis represses genes for cell surface and extracellular functions. J. Bacteriol. 187, 2010–2019 (2005).

- 29.

Smits, W. K. & Grossman, A. D. The transcriptional regulator Rok binds A+T-rich DNA and is involved in repression of a mobile genetic element in Bacillus subtilis. PLoS Genet. 6, e1001207 (2010).

- 30.

Duan, B. et al. How bacterial xenogeneic silencer rok distinguishes foreign from self DNA in its resident genome. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, 10514–10529 (2018).

- 31.

Slager, J., Kjos, M., Attaiech, L. & Veening, J. W. Antibiotic-induced replication stress triggers bacterial competence by increasing gene dosage near the origin. Cell 157, 395–406 (2014).

- 32.

Karaboja, X. et al. XerD unloads bacterial SMC complexes at the replication terminus. Mol. Cell 81, 756–766 (2021).

- 33.

Murray, H. & Koh, A. Multiple regulatory systems coordinate DNA replication with cell growth in Bacillus subtilis. PLoS Genet. 10, e1004731 (2014).

- 34.

Trussart, M. et al. Defined chromosome structure in the genome-reduced bacterium Mycoplasma pneumoniae. Nat. Commun. 8, 14665 (2017).

- 35.

Dixon, J. R. et al. Topological domains in mammalian genomes identified by analysis of chromatin interactions. Nature 485, 376–380 (2012).

- 36.

Kovács, Á. T. & Kuipers, O. P. Rok regulates yuaB expression during architecturally complex colony development of Bacillus subtilis 168. J. Bacteriol. 193, 998–1002 (2011).

- 37.

Hadjur, S. et al. Cohesins form chromosomal cis-interactions at the developmentally regulated IFNG locus. Nature 460, 410–413 (2009).

- 38.

Ghirlando, R. & Felsenfeld, G. CTCF: making the right connections. Genes Dev. 30, 881–891 (2016).

- 39.

Hu, G. et al. Systematic screening of CTCF binding partners identifies that BHLHE40 regulates CTCF genome-wide distribution and long-range chromatin interactions. Nucleic Acids Res. 48, 9606–9620 (2020).

- 40.

Liu, Z., Scannell, D. R., Eisen, M. B. & Tjian, R. Control of embryonic stem cell lineage commitment by core promoter factor, TAF3. Cell 146, 720–731 (2011).

- 41.

Qiu, Z. et al. Functional interactions between NURF and Ctcf regulate gene expression. Mol. Cell. Biol. 35, 224–237 (2015).

- 42.

Donohoe, M. E., Zhang, L. F., Xu, N., Shi, Y. & Lee, J. T. Identification of a Ctcf cofactor, Yy1, for the X chromosome binary switch. Mol. Cell 25, 43–56 (2007).

- 43.

Guastafierro, T. et al. CCCTC-binding factor activates PARP-1 affecting DNA methylation machinery. J. Biol. Chem. 283, 21873–21880 (2008).

- 44.

Stik, G. et al. CTCF is dispensable for immune cell transdifferentiation but facilitates an acute inflammatory response. Nat. Genet. 52, 655–661 (2020).

- 45.

Zhang, D. et al. Alteration of genome folding via contact domain boundary insertion. Nat. Genet. 52, 1076–1087 (2020).

- 46.

Goosen, N. & van de Putte, P. The regulation of transcription initiation by integration host factor. Mol. Microbiol. 16, 1–7 (1995).

- 47.

Wang, X. et al. Condensin promotes the juxtaposition of DNA flanking its loading site in Bacillus subtilis. Genes Dev. 29, 1661–75 (2015).

- 48.

Soh, Y. M. et al. Self-organization of parS centromeres by the ParB CTP hydrolase. Science 366, 1129–1133 (2019).

- 49.

Graham, T. G. W. et al. ParB spreading requires DNA bridging. Genes Dev. 28, 1228–38 (2014).

- 50.

Funnell, B. E. ParB partition proteins: complex formation and spreading at bacterial and plasmid centromeres. Front. Mol. Biosci. 3, 44 (2016).

- 51.

Hao, N., Shearwin, K. E. & Dodd, I. B. Programmable DNA looping using engineered bivalent dCas9 complexes. Nat. Commun. 8, 1628 (2017).

- 52.

Hao, N., Shearwin, K. E. & Dodd, I. B. Positive and negative control of enhancer-promoter interactions by other DNA loops generates specificity and tunability. Cell Rep. 26, 2419–2433 (2019).

- 53.

Qin, L., Erkelens, A. M., Markus, D. & Dame, R. T. The B. subtilis Rok protein compacts and organizes DNA by bridging. Preprint at bioRxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/769117 (2019).

- 54.

van der Valk, R. A. et al. Mechanism of environmentally driven conformational changes that modulate H-NS DNA-bridging activity. eLife 6, e27369 (2017).

- 55.

Chen, J. M. et al. Lsr2 of Mycobacterium tuberculosis is a DNA-bridging protein. Nucleic Acids Res. 36, 2123–2135 (2008).

- 56.

Cournac, A. & Plumbridge, J. DNA looping in prokaryotes: experimental and theoretical approaches. J. Bacteriol. 195, 1109–1119 (2013).

- 57.

Semsey, S., Tolstorukov, M. Y., Virnik, K., Zhurkin, V. B. & Adhya, S. DNA trajectory in the Gal repressosome. Genes Dev. 18, 1898–1907 (2004).

- 58.

Spizizen, J. Transformation of biochemically deficient strains of Bacillus subtilis by deoxyribonucleate. Proc. Natl Acad. Sci. USA 44, 1072–1078 (1958).

- 59.

Jahn, N., Brantl, S. & Strahl, H. Against the mainstream: the membrane-associated type I toxin BsrG from Bacillus subtilis interferes with cell envelope biosynthesis without increasing membrane permeability. Mol. Microbiol. 98, 651–66 (2015).

- 60.

Dugar, G. et al. High-resolution transcriptome maps reveal strain-specific regulatory features of multiple Campylobacter jejuni isolates. PLoS Genet. 9, e1003495 (2013).

- 61.

Afgan, E. et al. The Galaxy platform for accessible, reproducible and collaborative biomedical analyses: 2018 update. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, W537–W544 (2018).

- 62.

Bolger, A. M., Lohse, M. & Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: a flexible trimmer for Illumina sequence data. Bioinformatics 30, 2114–2120 (2014).

- 63.

Langmead, B. & Salzberg, S. L. Fast gapped-read alignment with Bowtie 2. Nat. Methods 9, 357–359 (2012).

- 64.

Ramírez, F. et al. deepTools2: a next generation web server for deep-sequencing data analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, W160–165 (2016).

- 65.

Liao, Y., Smyth, G. K. & Shi, W. FeatureCounts: an efficient general purpose program for assigning sequence reads to genomic features. Bioinformatics 30, 923–930 (2014).

- 66.

Crémazy, F. G. et al. Determination of the 3D genome organization of bacteria using Hi-C. Methods Mol. Biol. 1837, 3–18 (2018).

- 67.

Wolff, J. et al. Galaxy HiCExplorer: a web server for reproducible Hi-C data analysis, quality control and visualization. Nucleic Acids Res. 46, W11–W16 (2018).

- 68.

Hofmann, A., Müggenburg, J., Crémazy, F. & Heermann, D. W. Bekvaem: integrative data explorer for Hi-C data. J. Bioinform. Genom. https://doi.org/10.18454/jbg.2019.2.11.1 (2019).

- 69.

Comments

Post a Comment